Introduction

The land historically referred to as Israel and Palestine has been at the crossroads of civilizations for thousands of years. Its rich and complex history reflects the stories of many peoples, cultures, and faiths who have lived, governed, and cherished it across millennia. From ancient kingdoms to modern political developments, this region’s past continues to shape its present and future.

This page offers a comprehensive exploration of the land’s historical journey, tracing major civilizations, cultural identities, political transitions, and legal frameworks that have defined it over time. Through a detailed timeline, examination of cultural ties, an overview of political history, and a historical evaluation based on evidence and international perspectives, we seek to provide a deeper understanding of the land’s enduring significance.

Our aim is to present a clear, fact-based account that acknowledges the complexities of the region’s history. By exploring its layered past, readers can better appreciate the historical roots, cultural connections, and political realities that continue to influence discussions today.

Timeline

Explore a chronological journey through the history of the land, from early settlements to modern statehood. Click any box below to jump to that historical period.

Early Settlement & Prehistoric Roots (~10,000 BCE – 3500 BCE)

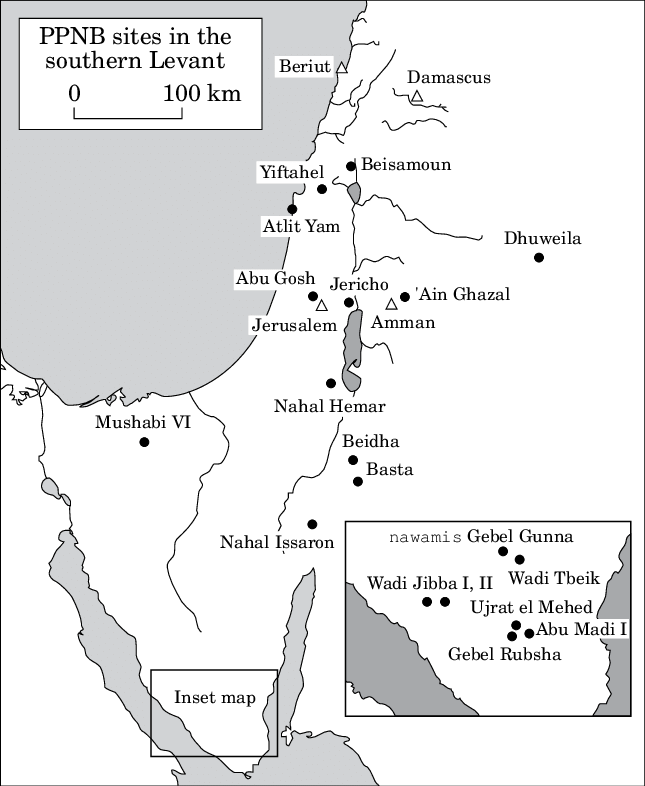

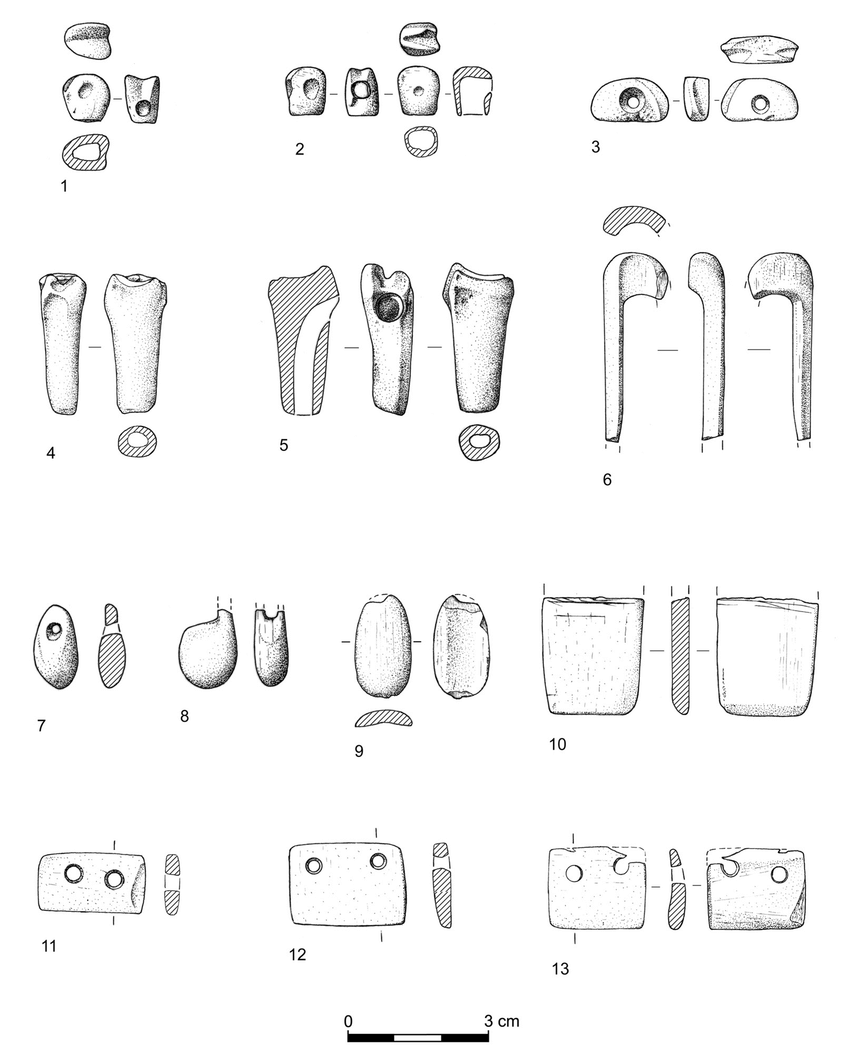

The earliest evidence of human settlement in the land now referred to as Israel and Palestine dates back to the Epipaleolithic and Neolithic periods. Archaeological discoveries in areas such as Jericho — one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world — reveal permanent structures, early agricultural practices, and rudimentary social organization as far back as 10,000 BCE.

These early communities developed along the Jordan Valley and the coastal plain, using the region’s fertile land and strategic geography to establish farming settlements and trade routes. The Natufian culture, a Mesolithic society, played a significant role in this formative stage of human development in the Levant.

While no national or tribal identity had yet emerged, the historical continuity of settlement in this region laid the foundation for later civilizations that would form lasting cultural and political ties to the land.

Video: The Incredible 11,000-Year-Old Tower of Jericho (via YouTube, Ancient Architects)

Canaanite City-States (~3500 BCE – 1200 BCE)

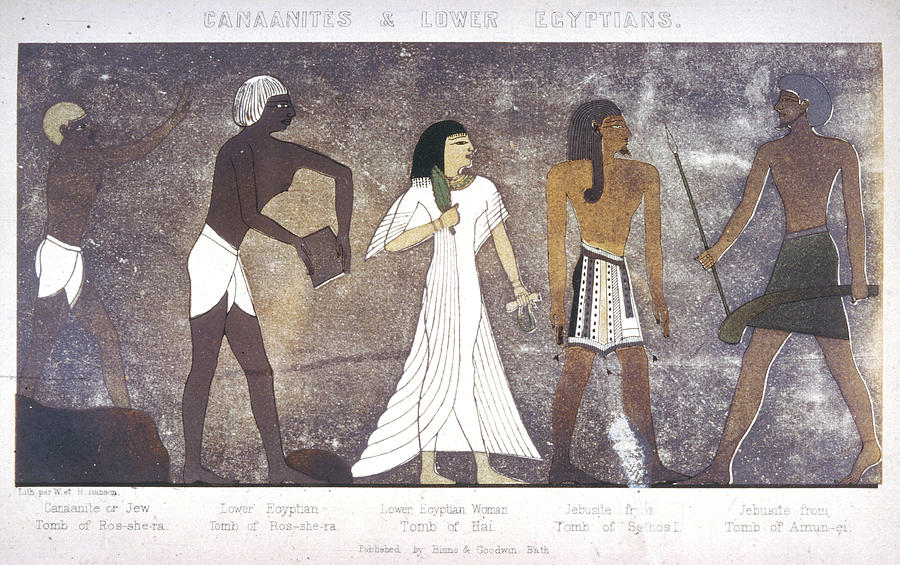

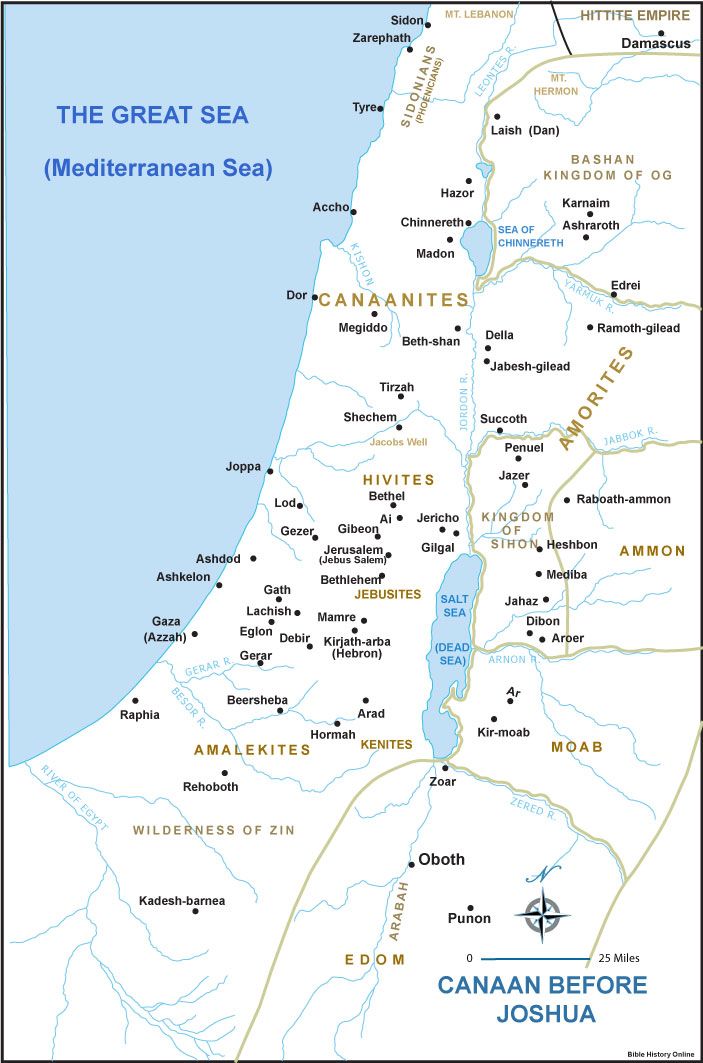

During the Early Bronze Age, the region saw the rise of independent Canaanite city-states. These fortified urban centers such as Hazor, Megiddo, and Arad developed advanced administrative systems, trade routes, and religious practices. They existed as politically independent polities, yet culturally shared in language, art, and religion.

Egyptian texts from the 2nd millennium BCE frequently reference these cities, noting their wealth, diplomacy, and occasional subordination as vassal states. The famous Amarna letters provide a rare written window into the diplomacy between Canaanite rulers and Egyptian pharaohs.

Despite the prosperity of these cities, they faced consistent pressure from nomadic and tribal groups, such as the Habiru, and eventually suffered disruption or collapse in the late Bronze Age, a period often associated with the rise of the Israelites and other regional powers.

Egyptian Influence on Canaanite City-States (~1500 BCE – 1200 BCE)

During the Late Bronze Age, Egypt exerted powerful political and cultural influence across the Levant, including the region historically recognized as Palestine. Through both direct control and a vassal-state system, Canaanite city-states like Gaza, Jaffa, and Beth Shean came under Egyptian administration.

Archaeological discoveries such as the Egyptian-style architecture at Tel el-Far’ah (South) and Egyptian stelae found in Beit She’an demonstrate the extent of imperial presence in the region. The Amarna Letters further reveal direct correspondence between local rulers and the Egyptian court, indicating a complex and deeply embedded administrative network.

Although Egyptian dominance waned toward the end of the Late Bronze Age, its cultural legacy endured in local religion, art, and governance across Canaanite Palestine. This set the stage for the political reshuffling that followed the eventual collapse of the Bronze Age world.

Video: Egyptian Influence in Canaan – Late Bronze Age (via YouTube)

Amarna Period (~1350 BCE)

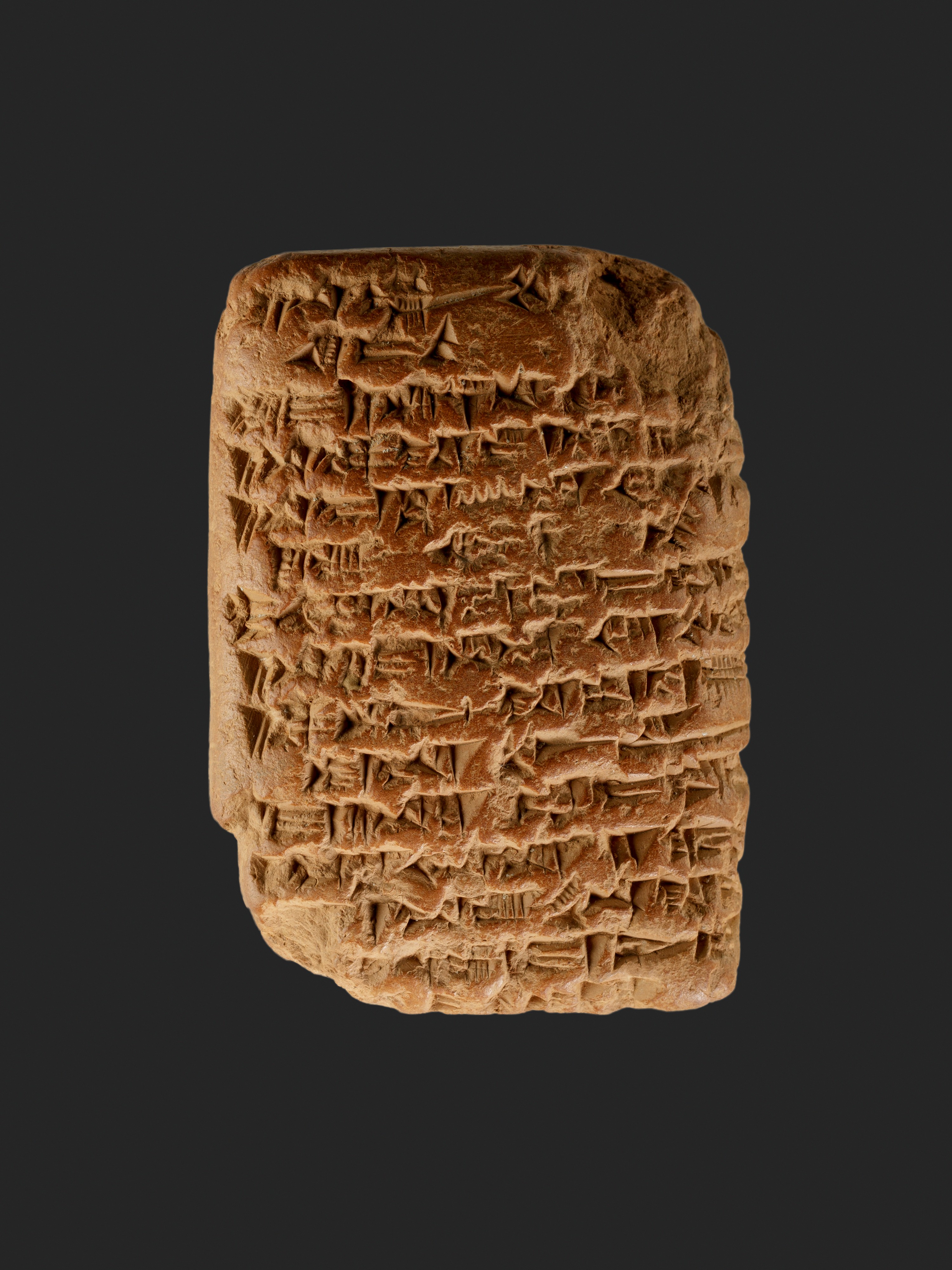

The Amarna Period marks a unique chapter in ancient Near Eastern diplomacy, characterized by the rich archive of clay tablets known as the Amarna Letters. These cuneiform texts, discovered in Egypt, include correspondence between Pharaoh Akhenaten and rulers of Canaanite city-states in what is now modern-day Palestine. The letters offer an unfiltered view of regional tensions, tribute, and appeals for military assistance.

These diplomatic tablets reveal that Canaanite rulers in Palestine viewed Egypt not only as a hegemon but also as a crucial arbiter in disputes with neighboring cities. Egyptian officials governed through appointed local rulers while maintaining minimal direct presence, relying instead on tribute systems and formal loyalty oaths.

The unique theology of Akhenaten, centered on the worship of Aten, had limited influence on Canaanite religion, but the broader diplomatic ties of the period helped establish language and bureaucratic conventions that would shape later Iron Age kingdoms in Palestine and beyond.

Video: The Amarna Letters – Conversations between Kings and Canaanites (via World History Encyclopedia)

Collapse of Canaanite Cities (~1200 BCE)

The Late Bronze Age collapse reshaped the political and cultural landscape of the ancient Near East. Around 1200 BCE, many Canaanite city-states in the region historically referred to as Palestine suffered catastrophic decline, destruction, or total abandonment. This wave of collapse occurred in tandem with upheavals throughout the eastern Mediterranean.

Major cities like Hazor and Lachish show archaeological evidence of violent destruction layers dating to this period. Theories for the collapse include climate change, widespread famine, invasions by the so-called “Sea Peoples,” internal rebellions, and systemic breakdowns in trade and administration.

Despite the collapse, not all sites vanished completely. Some urban centers were resettled in the Iron Age by new populations, including the Israelites, Philistines, and Arameans. The transition from the Late Bronze to the Iron Age is considered a pivotal moment in the ancient history of Palestine.

Video: 1177 BC – The Year Civilization Collapsed (via TED-Ed)

Rise of the Israelites (~1200–1000 BCE)

Following the collapse of the major Canaanite city-states around 1200 BCE, the highlands of central Palestine saw the emergence of small, dispersed settlements. Archaeological evidence from these areas suggests the rise of new ethnic and tribal groups—among them the Israelites—who would later become central figures in biblical and regional history.

Their settlement patterns, pottery, and architecture differ from earlier Canaanite urban models, pointing to a cultural shift rather than simple continuity. This has led many scholars to suggest the Israelites originated locally, possibly from marginalized Canaanite populations who moved into the highlands following regional upheaval.

By around 1000 BCE, some of these groups began to coalesce into tribal coalitions, laying the foundation for a more unified identity. The biblical accounts of Judges and early Kings may reflect memory of this transformation from loose clans to a centralized kingdom, beginning with Saul and solidifying under David in Jerusalem.

Video: The Origins of the Israelites (via World History Encyclopedia)

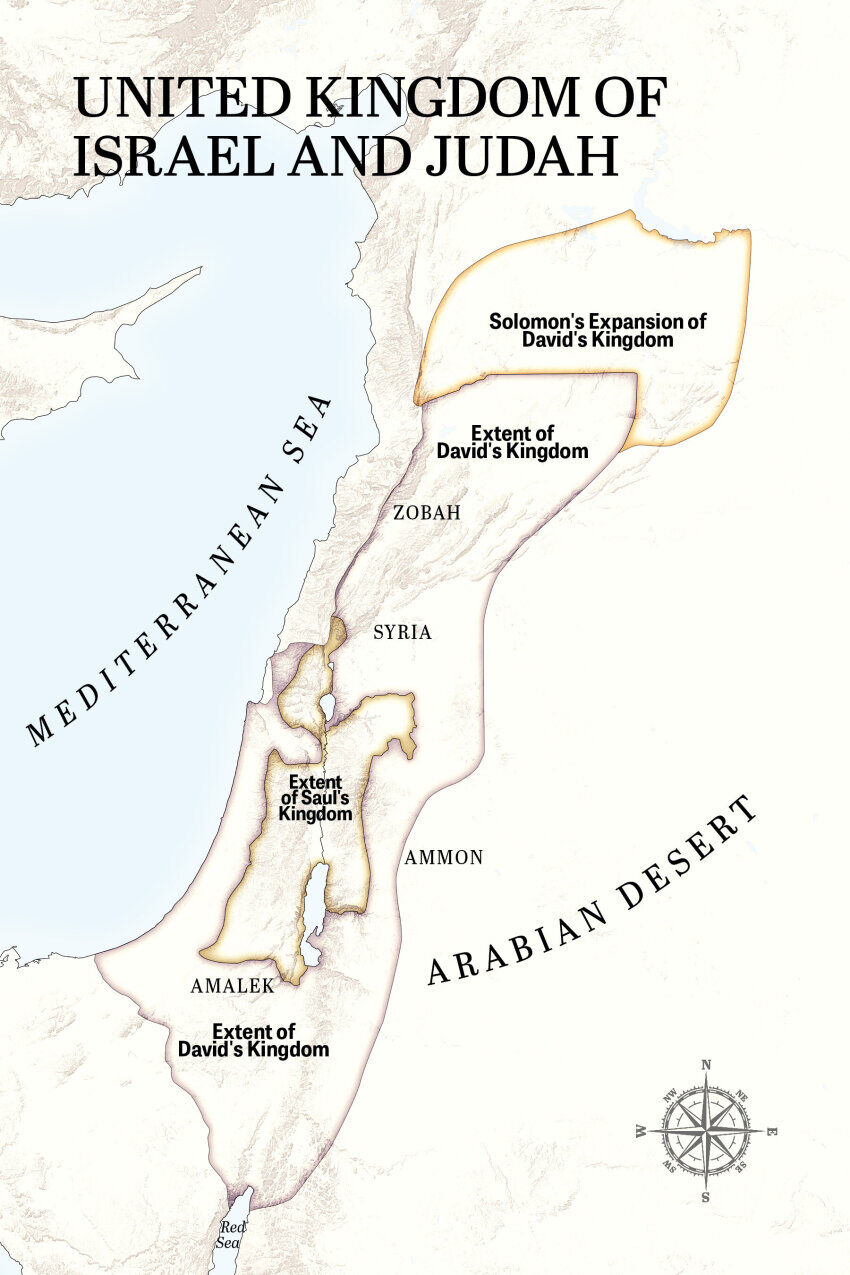

United Monarchy (~1000–922 BCE)

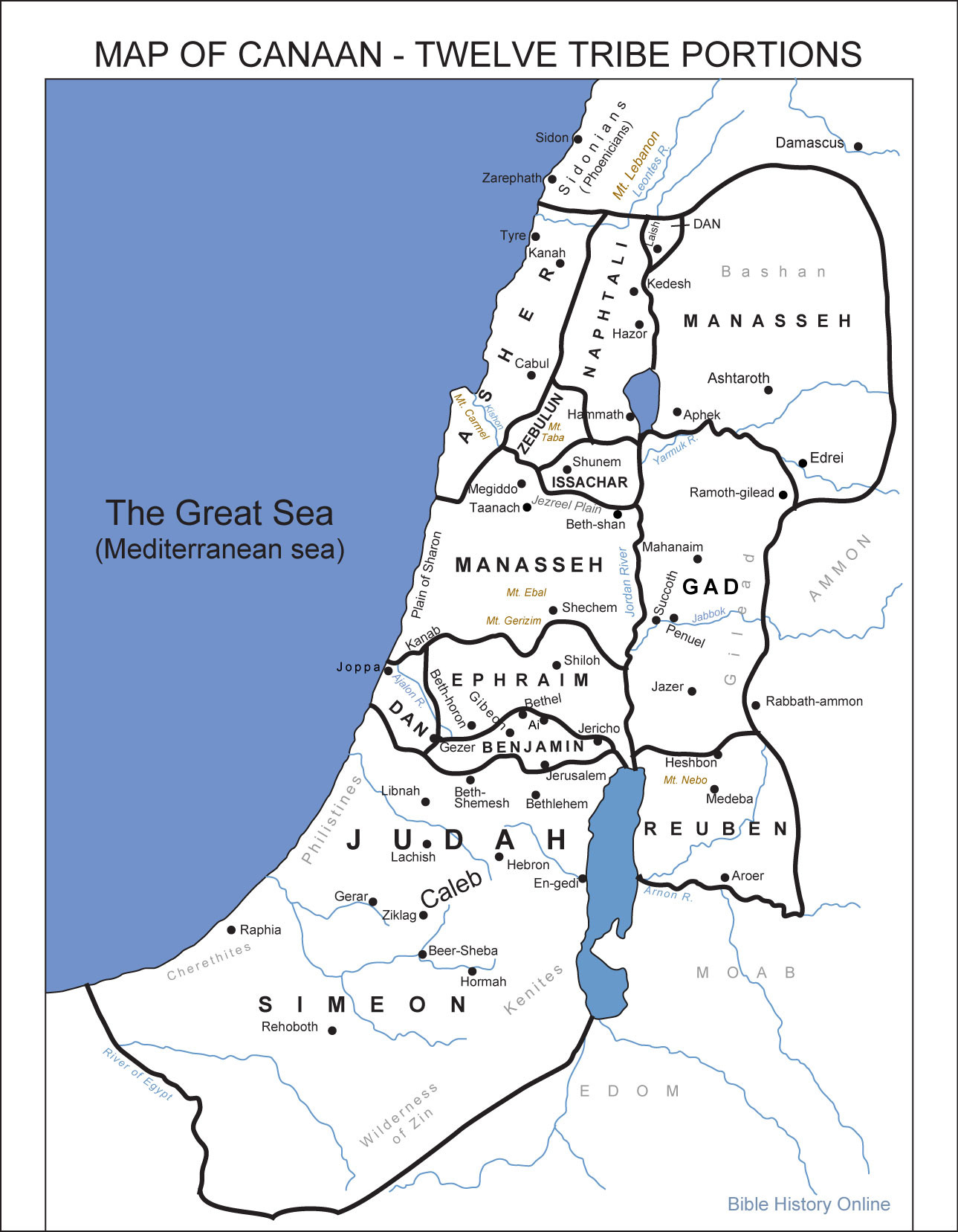

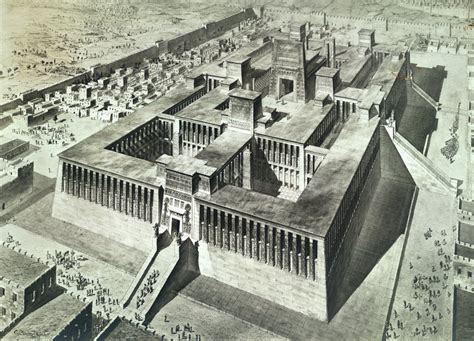

The United Monarchy refers to the period in which the tribes of Israel were unified under a single kingdom led by Saul, David, and Solomon. This was a formative moment in the political and religious development of ancient Palestine, as Jerusalem rose to prominence and centralized governance was briefly achieved.

David’s military conquests expanded the kingdom’s borders, while Solomon’s reign ushered in a period of relative peace and monumental building—including the First Temple in Jerusalem. Archaeological sites such as Khirbet Qeiyafa and findings at Tel Dan may support aspects of the biblical narrative, though scholarly debate continues.

Solomon’s temple, described in the Book of Kings, became the spiritual center of the Israelite religion and remains central to Jewish identity. His alliances and economic networks elevated the kingdom to a regional power—albeit briefly.

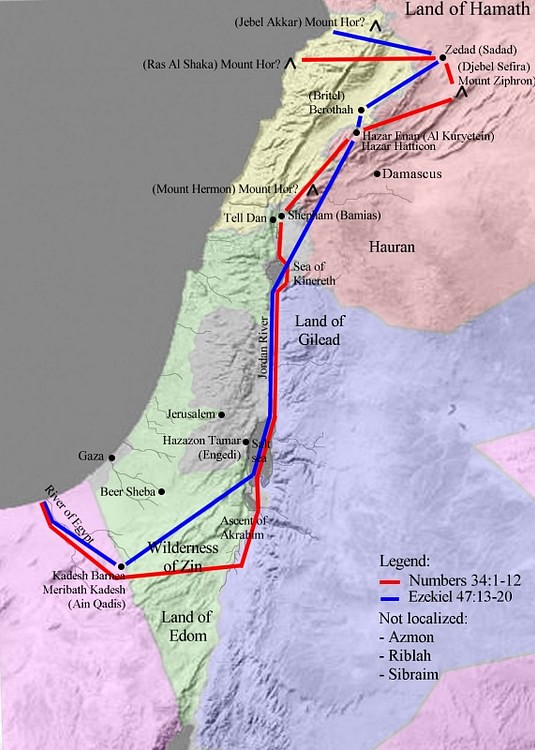

After Solomon’s death, internal tensions led to the division of the kingdom into northern Israel and southern Judah, ending the brief period of unity and setting the stage for centuries of regional conflict and identity formation in the land of Palestine.

Video: King David and the United Monarchy (via Unpacked)

Divided Kingdom (~930–722 BCE)

Following King Solomon’s death, the united monarchy fractured into two distinct entities: the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah. This division was precipitated by political dissent and differing visions for the future of the Israelite people.

The Kingdom of Israel, comprising ten tribes, established its capital in Samaria, while the Kingdom of Judah, consisting of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin, retained Jerusalem as its capital. This schism led to divergent political and religious developments in the region.

Throughout this period, both kingdoms faced internal challenges and external threats. Prophets emerged to guide and admonish the people, emphasizing the importance of faithfulness and justice.

The northern kingdom eventually fell to the Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE, leading to the exile of many Israelites. The southern kingdom persisted longer but faced its own challenges, setting the stage for subsequent historical developments in the region.

Video: A Kingdom Divided – The Fall of Israel (via Unpacked)

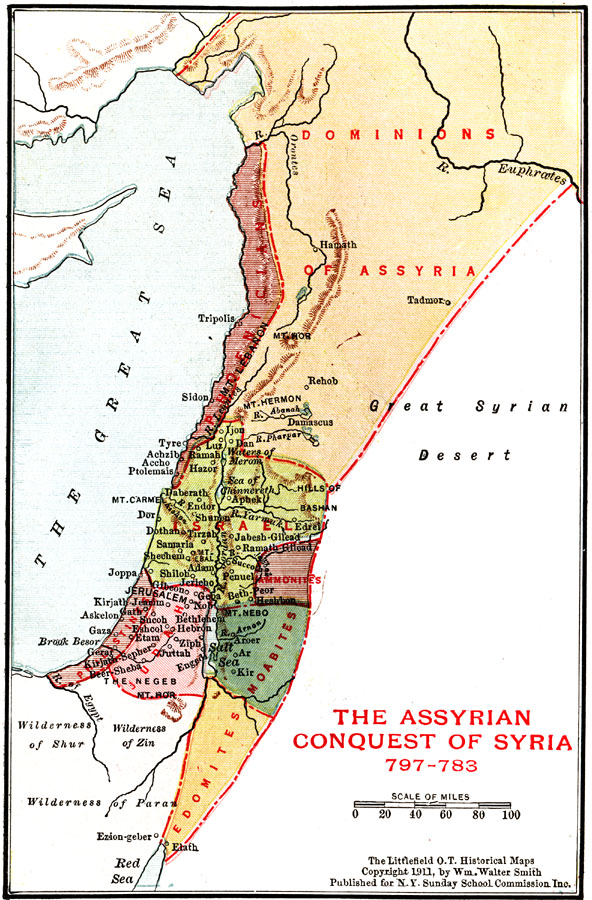

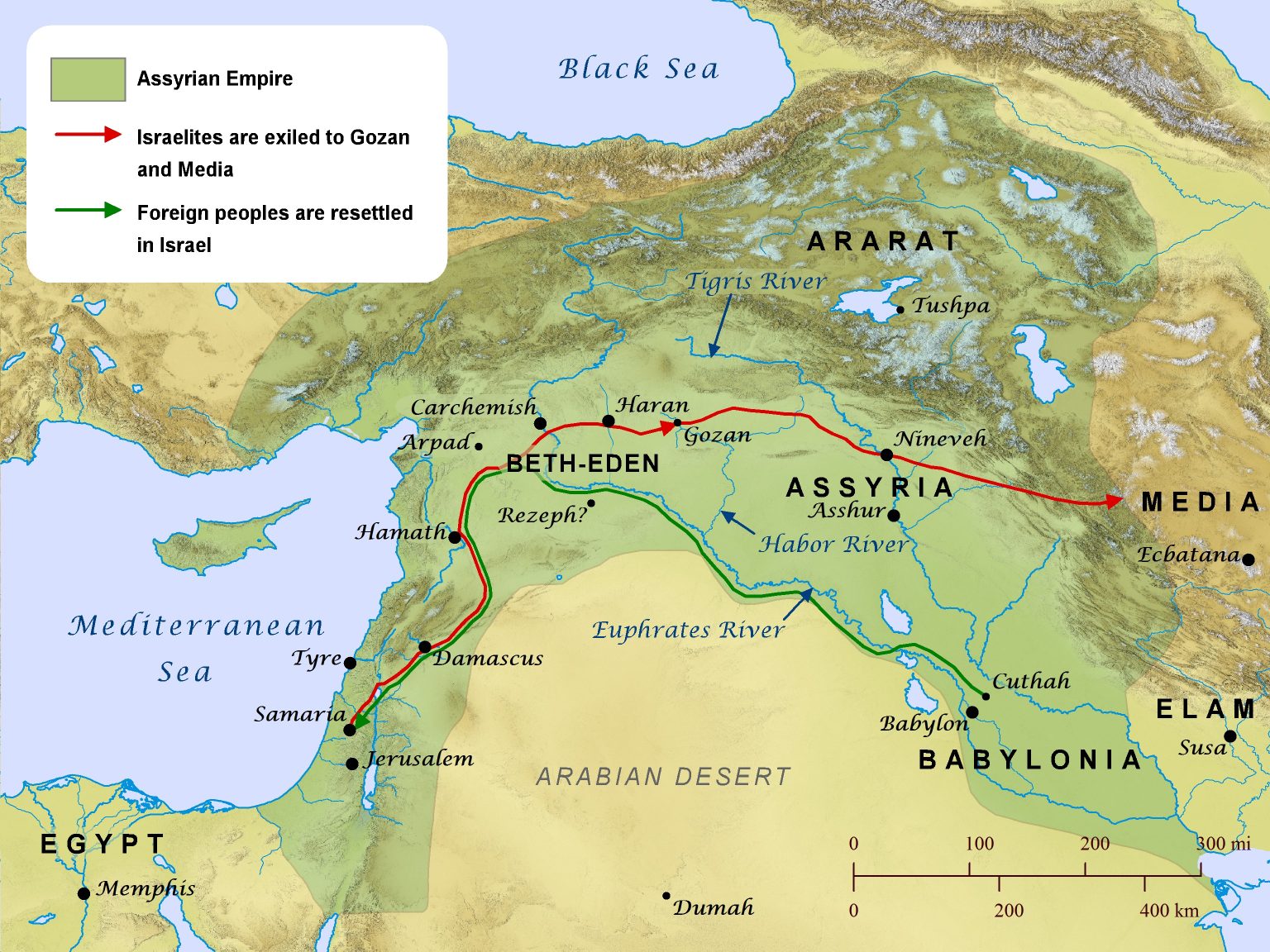

Assyrian Conquest (~740–722 BCE)

The Assyrian Empire, one of the most formidable powers of the ancient Near East, turned its attention to the Kingdom of Israel in the 8th century BCE. After years of tribute and vassalage, the northern kingdom was finally conquered by Assyria in 722 BCE. This marked the end of Israel’s sovereignty and the beginning of mass deportations.

Historical records and archaeological findings confirm that Sargon II and Tiglath-Pileser III imposed harsh control over the region. Tens of thousands of Israelites were forcibly relocated, an event often referred to as the “Lost Tribes of Israel.” These deportations reshaped the demographics of Palestine for centuries.

While Judah to the south managed to remain independent for a while longer, the northern kingdom’s destruction left a significant cultural and religious vacuum in ancient Palestine. The prophets Hosea and Amos had warned of the collapse, and their writings remain among the earliest prophetic texts in the Hebrew Bible.

The Assyrian conquest was not merely a military operation—it was a transformation of the political and ethnic landscape of the Levant. It set the stage for later tensions and reconfigurations that continued through Babylonian, Persian, and eventually Roman control.

Video: The Assyrian Invasion of Israel (via Jewish History Lab)

Babylonian Conquest (~586 BCE)

In 586 BCE, the Babylonian Empire under King Nebuchadnezzar II captured Jerusalem, marking a catastrophic moment in the history of ancient Judah. The conquest brought the destruction of Solomon’s Temple, widespread devastation, and the beginning of the Babylonian Exile—one of the most pivotal displacements in the history of ancient Palestine.

Babylonian forces systematically dismantled the infrastructure of the kingdom. Temple artifacts were seized, walls torn down, and thousands of Judeans—including the political and religious elite—were forcibly relocated to Babylon. This exile dramatically reshaped Jewish identity, literature, and theology.

Prophets like Jeremiah and Ezekiel documented the trauma and hope of the people during this time. Their writings became foundational to both biblical narrative and Jewish resilience during diaspora. The exile also introduced exposure to Mesopotamian culture, influencing subsequent religious and cultural developments.

Despite the devastation, the Babylonian Exile set the stage for theological reform and collective memory that would survive through Persian restoration and beyond. The connection to the land, the temple, and identity would remain central to the Judean people—even in displacement.

Video: Evidence for Judean Exiles in Babylonia (via UC Berkeley)

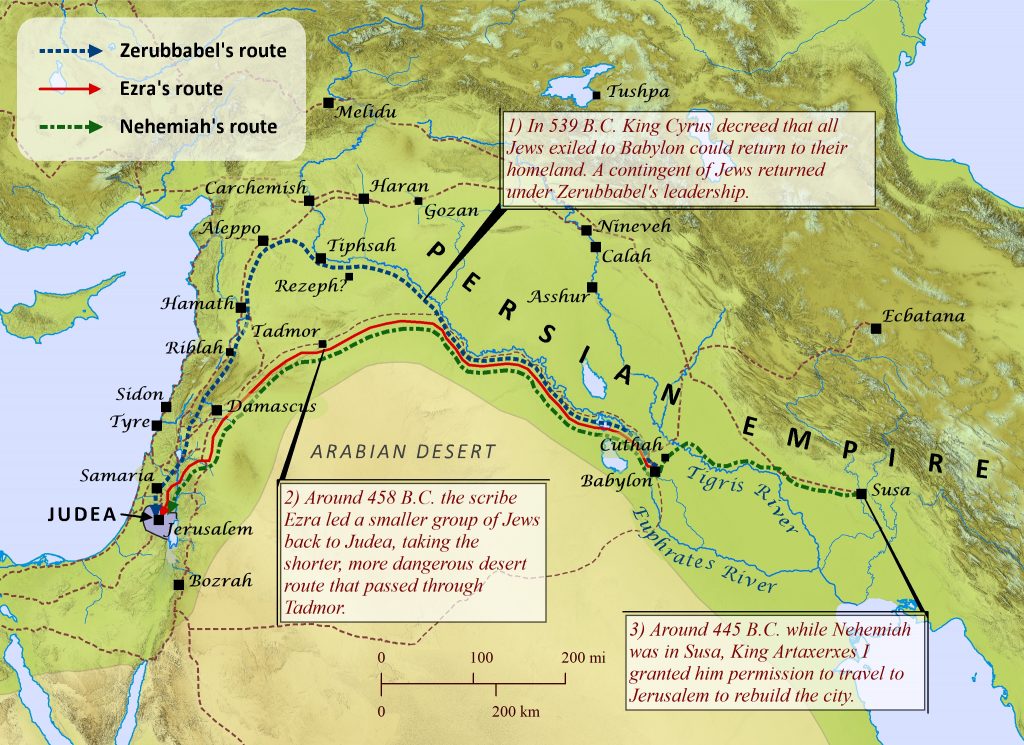

Persian Restoration (~539–400 BCE)

After conquering Babylon in 539 BCE, the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued a decree allowing exiled populations—including the Judeans—to return to their ancestral lands. This marked the beginning of the Persian Restoration period, a turning point in the religious and cultural continuity of ancient Palestine.

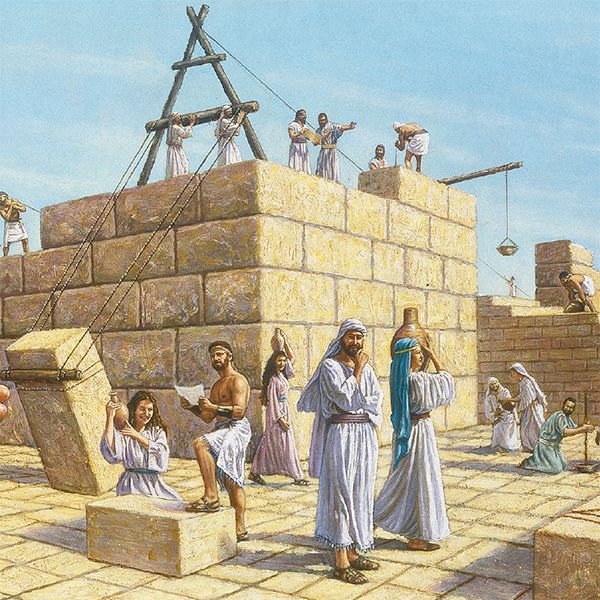

The returnees faced immense hardship, rebuilding homes, farms, and their sacred temple in Jerusalem. The construction of the Second Temple began around 516 BCE under Persian sponsorship, symbolizing both restoration and resilience. This temple would remain central to Jewish life for centuries.

The return from exile wasn’t a single mass event but occurred in phases. Multiple waves of Judeans returned across decades, as documented in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. These leaders not only restored physical structures but also reestablished religious practices and codified key elements of what would become post-exilic Judaism.

This period saw the emergence of new religious authority centered on Torah observance, priestly leadership, and community structure. Persian support allowed Jerusalem to flourish again, but autonomy remained limited. Nevertheless, the restoration solidified the link between identity, faith, and homeland in Jewish thought.

Video: The Decree of Cyrus the Great to Rebuild Jerusalem (via Bible History)

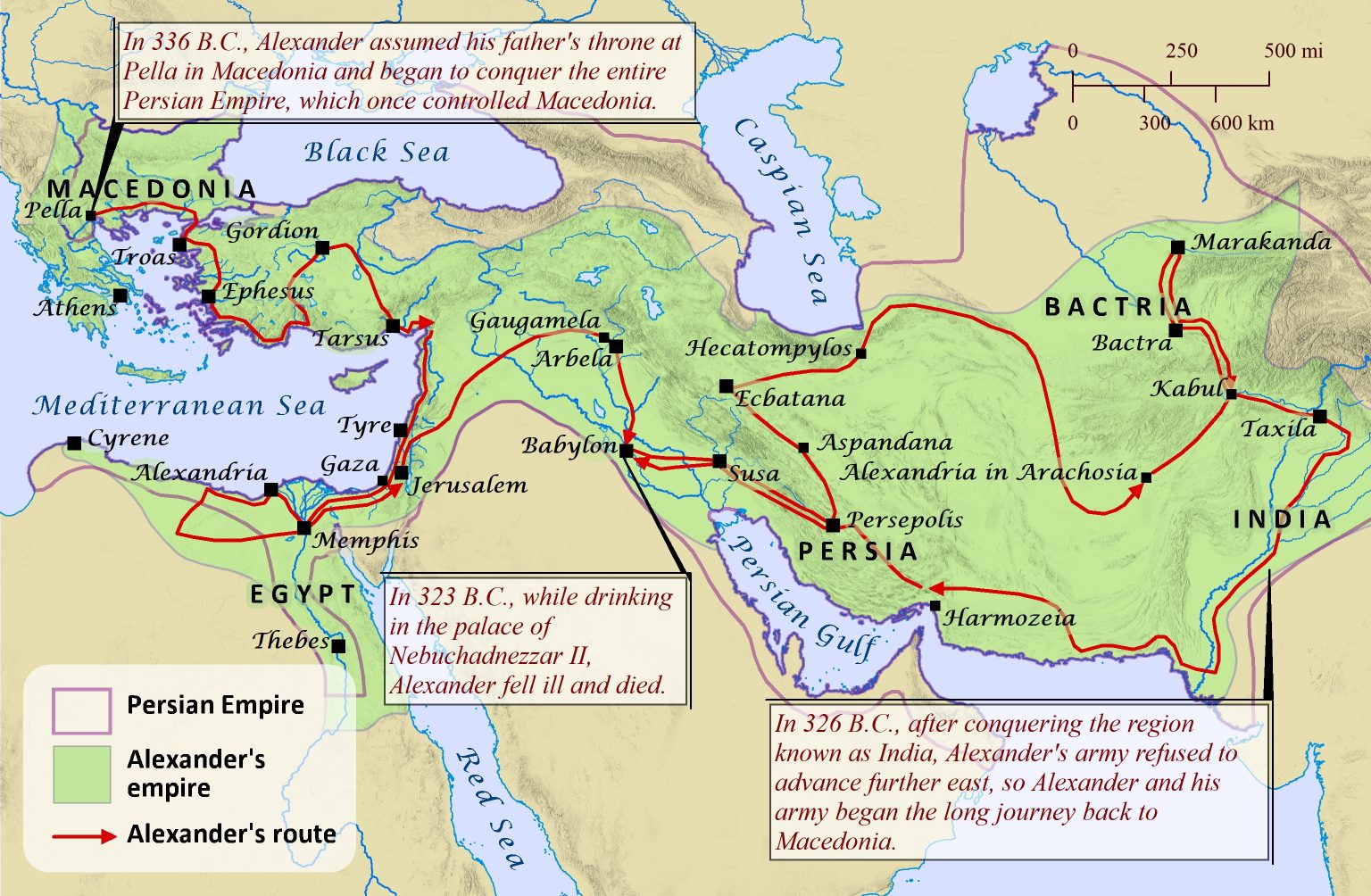

Greek Conquest (~332 BCE)

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great swept through the eastern Mediterranean and conquered Palestine as part of his larger campaign against the Persian Empire. This began a new chapter of Hellenistic influence across the region, introducing Greek language, art, architecture, and political philosophy.

Alexander’s interactions with the local population are shrouded in legend. Some Jewish traditions describe him entering Jerusalem peacefully and acknowledging the God of Israel, though these accounts are debated by historians. Regardless, Greek influence penetrated local institutions and culture deeply during this period.

Following Alexander’s death, his empire fractured, and Palestine became a contested zone between the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria. These power struggles shaped the political boundaries and cultural conflicts that would eventually lead to revolts and religious reformations in the region.

The Greek conquest introduced a new cultural era that shaped Jewish life and identity in both subtle and profound ways. Cities were rebuilt in Greek styles, gymnasiums were established, and Hellenistic values competed with traditional customs, setting the stage for future tensions between assimilation and religious integrity.

Video: Alexander’s Conquest of the Persian Empire (via Kings and Generals)

Seleucid Rule (~198–167 BCE)

After the fragmentation of Alexander the Great’s empire, Palestine came under the control of the Seleucid Empire. This shift brought renewed waves of Hellenistic influence, but also growing tensions between local Jewish traditions and imperial Greek culture.

The reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes marked a severe escalation. His aggressive policies included bans on Jewish religious practices, the desecration of the Second Temple, and the erection of Greek idols in sacred spaces. These actions fueled fierce opposition among the Jewish population.

This period culminated in the Maccabean Revolt, a landmark rebellion led by the Hasmonean family. It began in 167 BCE as a grassroots resistance to enforced Hellenization and ultimately succeeded in reclaiming the temple and establishing semi-independent Jewish rule.

The revolt is remembered during Hanukkah, a celebration of rededication and survival. It marked a unique period where Jewish autonomy returned to Palestine, albeit briefly, and the conflict served as a symbol of resistance against cultural erasure.

Video: The Maccabean Revolt and Seleucid Rule (via History Uncovered)

Hasmonean Rule (~140–37 BCE)

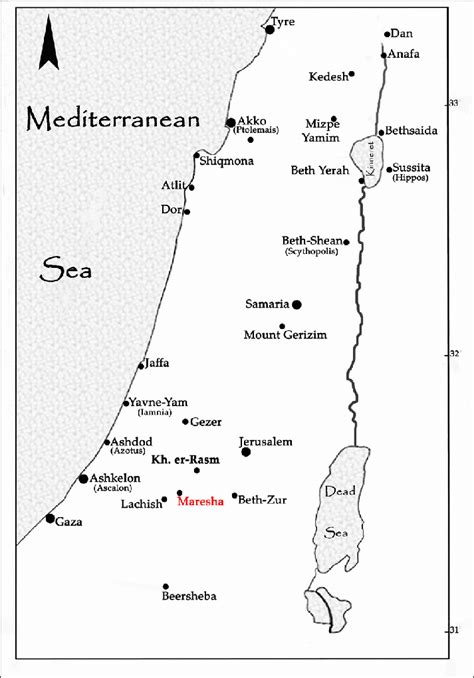

After the success of the Maccabean Revolt, the Hasmonean dynasty emerged as a powerful Jewish ruling family in Palestine. They established a semi-independent kingdom that expanded territory, centralized religious authority, and reasserted Jewish identity in the aftermath of Seleucid oppression.

Simon Thassi became the first official Hasmonean ruler in 140 BCE, solidifying both political leadership and high priestly control. This dual role fused governance and religion, creating a unique structure within Jewish history.

The Hasmoneans expanded Jewish control beyond Jerusalem, incorporating Edom, Galilee, and parts of Transjordan. They enforced religious uniformity and sometimes forcibly converted neighboring populations, sparking debate among later historians over their methods and legacy.

Despite periods of prosperity, the Hasmonean dynasty was weakened by internal strife, civil war, and factionalism. These divisions created the opening for Roman intervention, leading to the eventual downfall of the dynasty and the rise of Herodian rule under Roman oversight.

Video: The Hasmonean Dynasty (via History Uncovered)

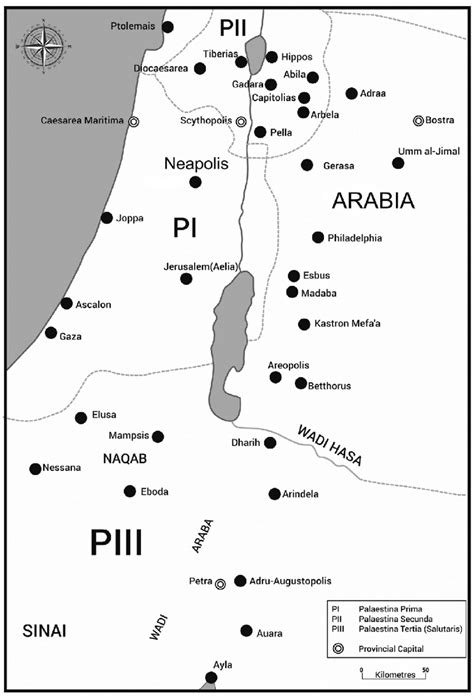

Roman Judea (~63 BCE–135 CE)

In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey entered Jerusalem, officially bringing the Hasmonean Kingdom under Roman control. This marked the beginning of the Roman period in Palestine, defined by shifting degrees of autonomy, military occupation, and social upheaval.

Rome installed client kings like Herod the Great, who ruled with significant autonomy but remained subordinate to imperial interests. Herod renovated the Second Temple, transforming it into one of the most impressive religious structures in the ancient world. Despite his achievements, his rule was marked by paranoia, executions, and heavy taxation.

Following Herod’s death, unrest intensified under direct Roman governance. Judea became a Roman province, and tensions between Roman authorities and the Jewish population escalated. These tensions culminated in the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), including the catastrophic siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The destruction of the Second Temple was a defining moment. Thousands were killed or enslaved, and the temple’s destruction permanently altered Jewish religious life. In the following decades, continued revolts led to the renaming of Judea as “Syria Palaestina” by the Romans in an attempt to erase Jewish connection to the land.

Video: The Roman Conquest of Judea (via History Uncovered)

Byzantine Period (~324–638 CE)

Following the division of the Roman Empire, Palestine became part of the Eastern Roman—or Byzantine—Empire. This era saw a profound transformation as Christianity became the dominant religion, influencing urban design, cultural practices, and political authority across the region.

Churches were constructed in major cities like Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Gaza. Religious pilgrimage became common, bringing new infrastructure and attention to sacred sites. This period also produced stunning mosaics that survive today as a testament to Byzantine artistic and spiritual expression.

Byzantine control emphasized Christian orthodoxy and centralized governance. However, Palestine remained a multi-ethnic and multi-religious region. Jews and Samaritans still lived in significant numbers, though often subject to religious suppression and rebellion.

Although prosperous for centuries, Byzantine Palestine began to decline with Sasanian invasions and later Arab-Islamic expansion. By 638 CE, Byzantine rule ended as the Rashidun Caliphate took control, marking the start of a new Islamic era in the region.

Video: The Byzantine Period in Palestine (via History Uncovered)

Islamic Caliphates (~638–1099 CE)

Following the Islamic conquest, Palestine became part of successive Islamic caliphates, including the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid dynasties. Each contributed to the region’s cultural, religious, and administrative development. The establishment of cities like Ramla and the construction of monumental architecture, such as the Dome of the Rock, underscored the significance of Palestine within the Islamic world. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE) emphasized the importance of Palestine by investing in infrastructure and religious sites. The Abbasid period (750–969 CE) saw a shift in administrative focus, yet Palestine remained a vital region, with cities like Jerusalem continuing to attract pilgrims and scholars. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

Under the Fatimid Caliphate (969–1099 CE), Palestine experienced both cultural flourishing and periods of conflict. The Fatimids’ rule was marked by architectural advancements and the patronage of arts, even as they contended with internal strife and external threats. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

Throughout these periods, Palestine remained a crossroads of cultures and religions, reflecting the diverse influences of its rulers and inhabitants. The legacy of the Islamic caliphates is evident in the region’s enduring architectural landmarks and historical narratives.

Video: The Islamic Caliphates in Palestine (via History Uncovered)

Crusader Period (~1099–1291 CE)

The Crusader Period began in 1099 CE with the conquest of Jerusalem by European forces during the First Crusade. This marked the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader states across the Levant, including much of Palestine. These territories were ruled by Latin Christian elites who introduced feudal governance and European architectural styles. ([source](https://fanack.com/palestine/history-of-palestine/crusaders/))

Despite initial military success, the Crusaders faced constant resistance from Muslim rulers and local populations. Cities such as Nablus, Bethlehem, and Jaffa were fortified, and new churches and castles were constructed to solidify their hold on the region. ([source](https://image-database.nes.lsa.umich.edu/items/browse?tags=Crusades))

The most iconic resistance came from Saladin, the Muslim military leader who recaptured Jerusalem in 1187 CE after the Battle of Hattin. This loss triggered the Third Crusade but ultimately marked the beginning of the end for Crusader control in Palestine. ([source](https://www.britannica.com/event/Crusades))

By 1291 CE, the last Crusader stronghold in Acre fell to Muslim forces, bringing an end to nearly two centuries of Crusader presence in Palestine. Though short-lived, the Crusader era left a lasting architectural and cultural imprint, visible in churches, fortifications, and chronicles from the time.

Video: The First Crusade – via History Uncovered

Mamluk Period (~1260–1516 CE)

The Mamluk period in Palestine began after the defeat of the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. The Mamluks, originally slave soldiers from Egypt, established their dominance over the Levant and maintained control of Palestine for more than 250 years. During this era, Jerusalem regained some of its prestige as an Islamic religious center, and large architectural projects flourished. ([source](https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/maml/hd_maml.htm))

Mamluk rulers invested heavily in religious and civic infrastructure. Schools (madrasas), inns (khans), and fountains (sabils) were constructed in key urban centers like Jerusalem, Hebron, and Gaza. The architectural style combined geometric intricacy with grand scale. ([source](https://palmuseum.org/en/exhibitions-and-events/events-m/book-launch-and-exhibition-jerusalem-mamluk-era-history-and))

The Mamluk administrative system was heavily militarized. They divided the region into districts and taxed agricultural outputs, sustaining a relatively stable, though often rigid, rule. They also repelled multiple Crusader and Mongol incursions, maintaining Islamic control over the Holy Land during a volatile time.

Despite moments of internal strife and periodic famine, the Mamluk period fostered religious scholarship and maintained the sanctity of Islamic sites. Their legacy is still evident in the urban fabric of Old Jerusalem and surrounding cities.

Video: The Mamluk Period in Palestine (via History Uncovered)

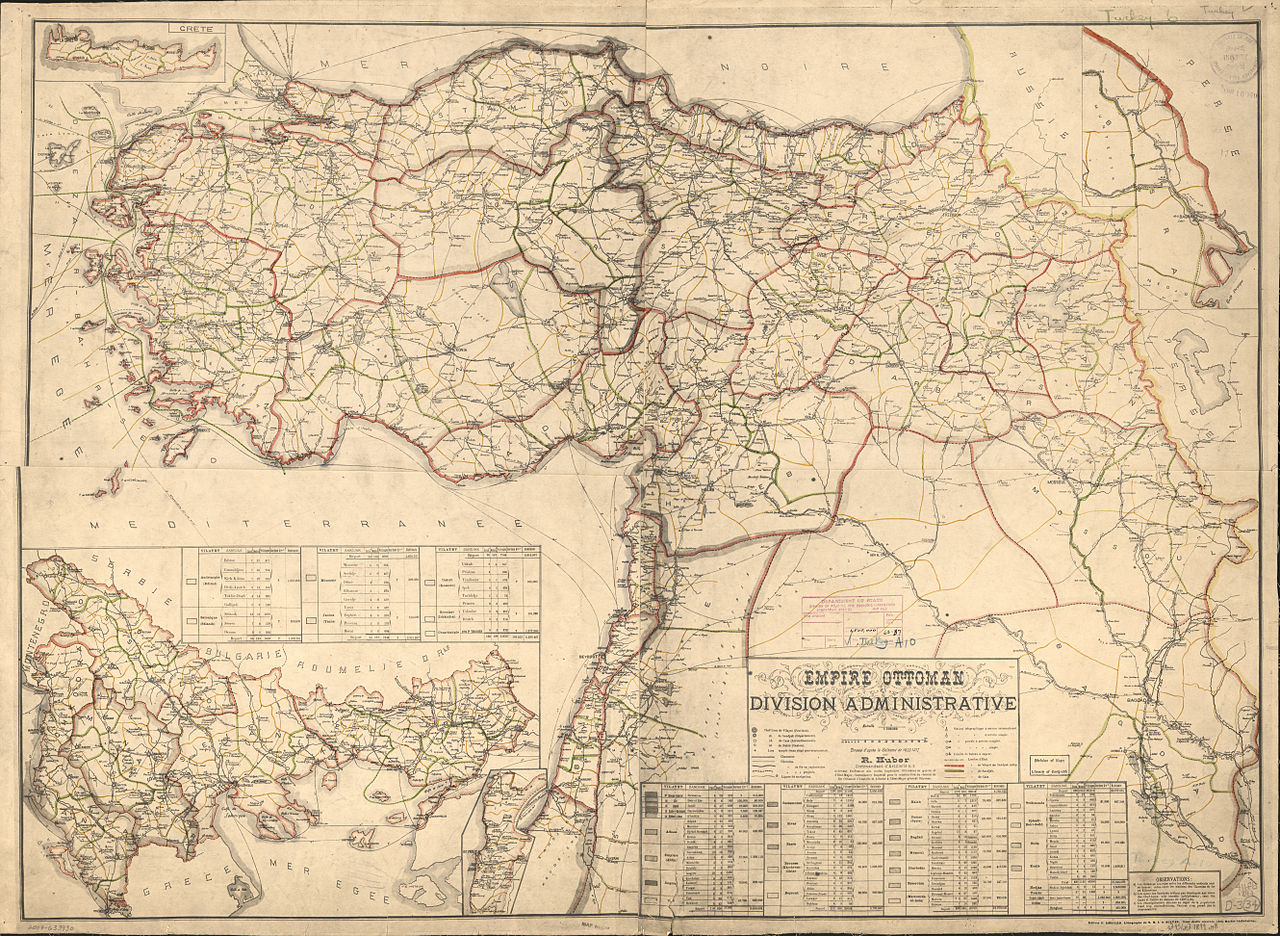

Ottoman Period (~1516–1917 CE)

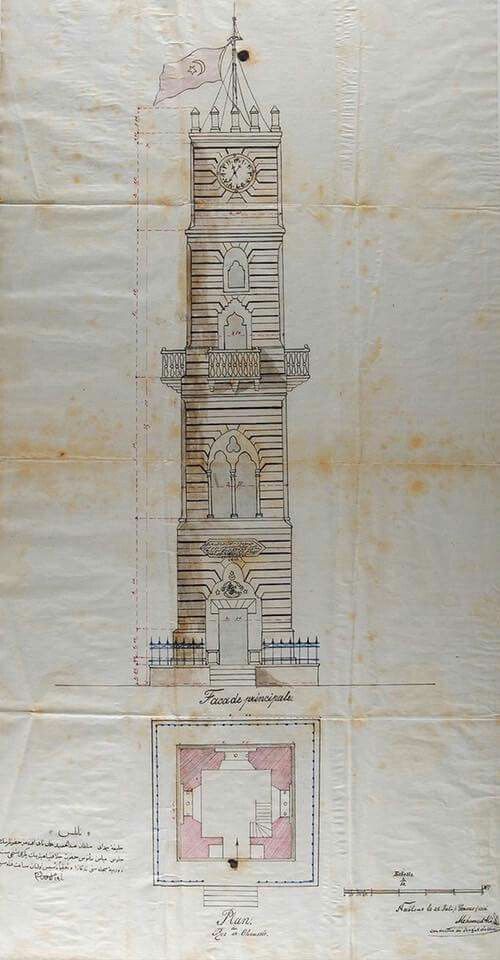

Following the defeat of the Mamluks at the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516, the Ottoman Empire incorporated Palestine into its realm. This ushered in four centuries of relatively stable rule, during which Palestine was organized into districts governed by appointed officials from Istanbul. The Ottomans restored Islamic holy sites and improved infrastructure throughout the region. ([source](https://turkpidya.com/ottoman-jerusalem-my-historical-research/))

Major cities such as Jerusalem, Nablus, Gaza, and Hebron grew under Ottoman patronage. Religious communities—Muslims, Christians, and Jews—were governed under the millet system, which granted them a degree of autonomy. Local Arab elites played key roles in administration and land management. ([source](https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/155/ottoman-territorial-reorganization-1840-1917))

Ottoman reforms in the 19th century included modernization of land ownership laws, census taking, and infrastructure projects like the Hejaz railway. These reforms created new tensions, as they shifted power balances and redefined relationships between local peasants and landowners. ([source](https://www.akhbarelbalad.net/ar/1/10/5176/?ls-art0=20))

By the late 19th century, Ottoman control weakened, and foreign powers—especially Britain, France, and Germany—increased their involvement in the region. Zionist immigration and land purchases began during this time, setting the stage for significant changes in the 20th century.

Video: The Ottoman Empire (via Kings and Generals)

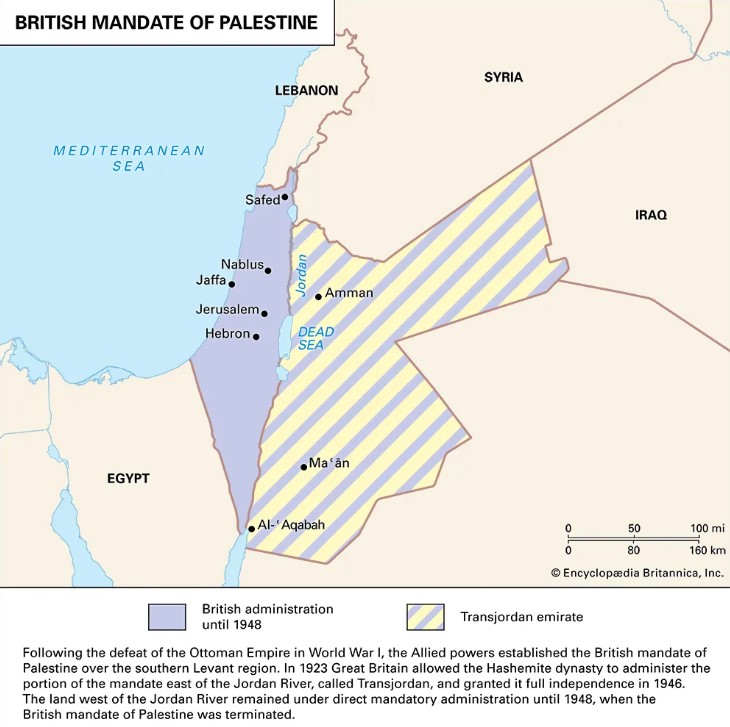

British Mandate Period (~1917–1948 CE)

Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Palestine came under British control via the League of Nations mandate system. The British Mandate formalized British administrative oversight, while simultaneously fueling conflicting national aspirations between the Arab population and the growing Jewish immigrant community. ([source](https://www.britannica.com/facts/mandate-League-of-Nations))

The 1917 Balfour Declaration expressed British support for a Jewish national home in Palestine, intensifying tensions with Arab communities who opposed mass Jewish immigration. Violence erupted in multiple waves during the 1920s and 1930s, prompting British restrictions and commissions of inquiry. ([source](https://www.jpost.com/Features/In-Thespotlight/This-Week-in-History-The-British-Mandate-for-Palestine))

Economic modernization progressed during this time, especially in infrastructure and urban design. British policies also introduced Western legal systems and zoning that shaped modern-day Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. However, rising unrest and global attention to the Jewish refugee crisis after the Holocaust made Palestine a focal point of international debate. ([source](https://www.archdaily.com/879399/social-construction-modern-architecture-in-british-mandate-palestine))

The Arab Revolt (1936–1939), Jewish underground resistance, and shifting British policies culminated in chaos by the 1940s. In 1947, the British declared their intention to withdraw and deferred the issue to the United Nations. This led to the UN Partition Plan and the end of the British Mandate in 1948.

Video: Britain in Palestine (via Kings and Generals)

Creation of Israel & 1948 War (~1947–1949 CE)

The modern State of Israel was established on May 14, 1948, following the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947, which recommended the division of British Mandate Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. The Jewish leadership accepted the plan, while the Arab League rejected it. The declaration of independence was quickly followed by military action from five Arab states. ([source](https://www.britannica.com/event/Arab-Israeli-wars))

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War, which Palestinians refer to as the Nakba (“catastrophe”), was not a spontaneous tragedy imposed by external forces, but rather the foreseeable outcome of decisions made by the Arab world’s political and military leadership. In 1947, the United Nations proposed a partition plan that would divide the British Mandate of Palestine into two states—one Jewish, one Arab. The Jewish leadership, though unhappy with the limited borders assigned to the Jewish state, accepted the compromise, recognizing it as a legitimate path to statehood and coexistence. The Arab states and the Arab Higher Committee, however, categorically rejected the plan, refusing any Jewish national presence in the region.

Instead of pursuing diplomacy or coexistence, they opted for confrontation. When Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, five Arab nations—Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq—immediately invaded the newly formed state, initiating a full-scale war. Their stated goal was the destruction of Israel and the prevention of Jewish sovereignty. This war, launched by Arab nations, led directly to the displacement of over 600,000 Palestinian Arabs.

While the suffering of those who were displaced is real and tragic, it is essential to recognize that their plight was not the result of an unprovoked expulsion by Israel, but a consequence of a war initiated by the Arab world—a war waged in rejection of a peaceful two-state solution. Had Arab leaders accepted the UN Partition Plan, both a Jewish and an Arab state would have come into existence peacefully in 1948. Instead, the Arab world gambled on a military solution and lost. The Nakba was not imposed upon the Palestinian people by unilateral Israeli aggression—it was a tragedy brought about by the very leaders who claimed to speak in their name. (source)

The war ended in 1949 with a series of armistice agreements, leaving Israel with recognized sovereignty over significant portions of former Mandatory Palestine. The result established the geopolitical foundation of the Israeli state and became a defining moment in the broader Israeli–Arab conflict. ([source](https://www.jta.org/2019/05/09/israel/9-rare-photos-from-israels-war-of-independence))

Though deeply contested and painful for many communities, this moment represents both the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty in their ancestral homeland and the beginning of a multi-decade struggle for Palestinian national identity.

Video: Israel at War – 1948 (via PragerU)